On October 14, 1947, the Bell X-1 became the first airplane to fly faster than the speed of sound, reaching a speed of 1,127 kilometers (700 miles) per hour, Mach 1.06, at an altitude of 13,000 meters (43,000 feet).

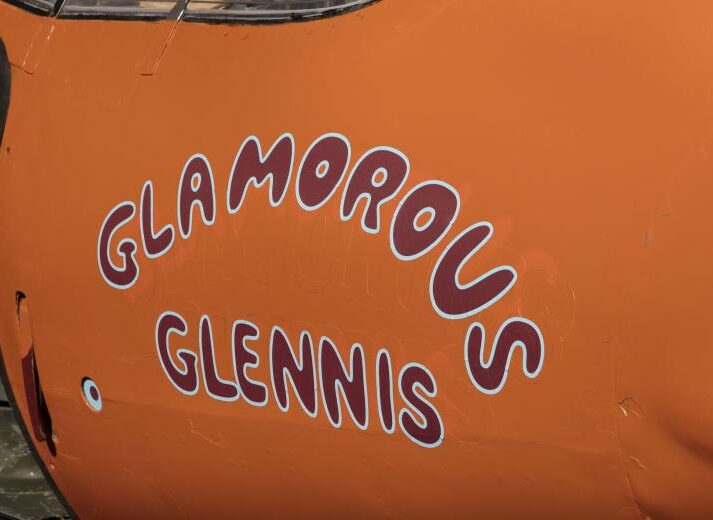

On October 14, 1947, the Bell X-1 became the first airplane to fly faster than the speed of sound, reaching a speed of 1,127 kilometers (700 miles) per hour, Mach 1.06, at an altitude of 13,000 meters (43,000 feet). Yeager named the airplane "Glamorous Glennis" in tribute to his wife.

Yeager named the airplane "Glamorous Glennis" in tribute to his wife. The X-1 air-launched at an altitude of 7,000 meters (23,000 feet) from the bomb bay of a Boeing B-29 and used its rocket engine to climb to its test altitude. On March 16, 1945, the Army Air Technical Service Command awarded the Bell Aircraft Corporation of Buffalo, New York, a contract to develop three transonic and supersonic research aircraft under project designation MX-653. The Army assigned the designation XS-1 for Experimental Sonic-1. Bell Aircraft built three rocket-powered XS-1 aircraft.

The X-1 air-launched at an altitude of 7,000 meters (23,000 feet) from the bomb bay of a Boeing B-29 and used its rocket engine to climb to its test altitude. On March 16, 1945, the Army Air Technical Service Command awarded the Bell Aircraft Corporation of Buffalo, New York, a contract to develop three transonic and supersonic research aircraft under project designation MX-653. The Army assigned the designation XS-1 for Experimental Sonic-1. Bell Aircraft built three rocket-powered XS-1 aircraft. It flew a total of 78 times, and on March 26, 1948, with Yeager at the controls, it attained a speed of 1,540 kilometers (957 miles) per hour, Mach 1.45, at an altitude of 21,900 meters (71,900 feet). This was the highest velocity and altitude reached by a piloted airplane up to that time.

It flew a total of 78 times, and on March 26, 1948, with Yeager at the controls, it attained a speed of 1,540 kilometers (957 miles) per hour, Mach 1.45, at an altitude of 21,900 meters (71,900 feet). This was the highest velocity and altitude reached by a piloted airplane up to that time. On March 16, 1945, the Army Air Technical Service Command awarded the Bell Aircraft Corporation of Buffalo, New York, a contract to develop three transonic and supersonic research aircraft under project designation MX-653. The Army assigned the designation XS-1 for Experimental Sonic-1. Bell Aircraft built three rocket-powered XS-1 aircraft.

On March 16, 1945, the Army Air Technical Service Command awarded the Bell Aircraft Corporation of Buffalo, New York, a contract to develop three transonic and supersonic research aircraft under project designation MX-653. The Army assigned the designation XS-1 for Experimental Sonic-1. Bell Aircraft built three rocket-powered XS-1 aircraft. The X-1 (originally called the XS-1) was developed as part of a cooperative program initiated in 1944 by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and the U.S. Army Air Forces (later the U.S. Air Force) to develop special manned transonic and supersonic research aircraft.

The X-1 (originally called the XS-1) was developed as part of a cooperative program initiated in 1944 by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and the U.S. Army Air Forces (later the U.S. Air Force) to develop special manned transonic and supersonic research aircraft. The XS-1 aircraft were constructed from high-strength aluminum, with propellant tanks fabricated from steel.

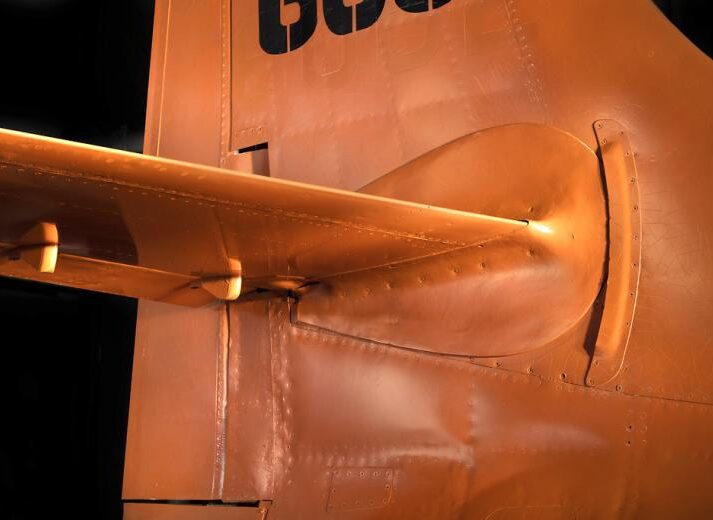

The XS-1 aircraft were constructed from high-strength aluminum, with propellant tanks fabricated from steel. The first two XS-1 aircraft did not utilize turbopumps for fuel feed to the rocket engine, relying instead on direct nitrogen pressurization of the fuel-feed system.

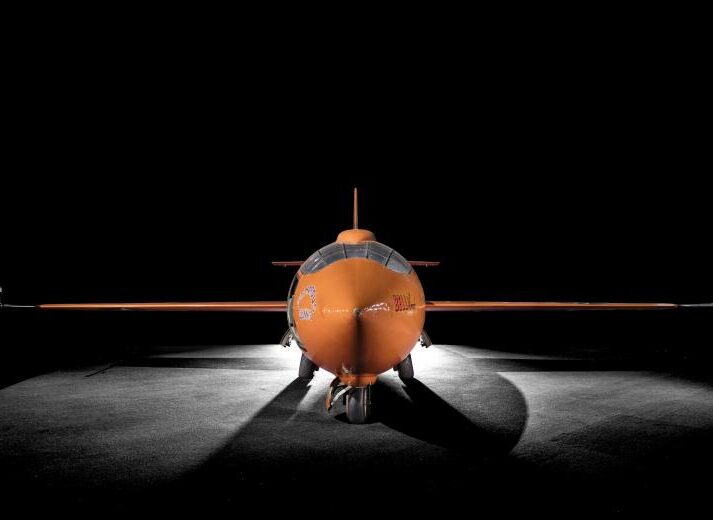

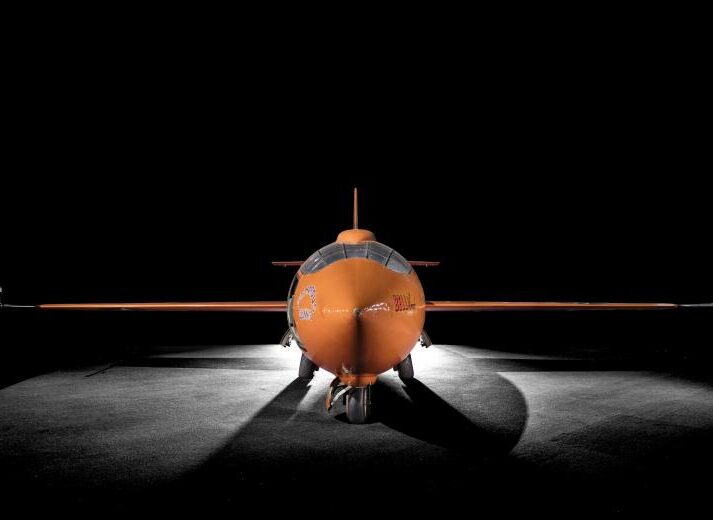

The first two XS-1 aircraft did not utilize turbopumps for fuel feed to the rocket engine, relying instead on direct nitrogen pressurization of the fuel-feed system. The smooth contours of the XS-1, patterned on the lines of a .50-caliber machine gun bullet, masked an extremely crowded fuselage containing two propellant tanks, twelve nitrogen spheres for fuel and cabin pressurization, the pilot’s pressurized cockpit, three pressure regulators, a retractable landing gear, the wing carry-through structure, a Reaction Motors, Inc., 6.000-pound-thrust rocket engine, and more than five hundred pounds of special flight-test instrumentation.

The smooth contours of the XS-1, patterned on the lines of a .50-caliber machine gun bullet, masked an extremely crowded fuselage containing two propellant tanks, twelve nitrogen spheres for fuel and cabin pressurization, the pilot’s pressurized cockpit, three pressure regulators, a retractable landing gear, the wing carry-through structure, a Reaction Motors, Inc., 6.000-pound-thrust rocket engine, and more than five hundred pounds of special flight-test instrumentation. On August 8,1949, Maj. Frank K. Everest, Jr., USAF, reached an altitude of 71,902 feet, the highest flight made by the little rocket airplane. It continued flight test operations until mid-1950, by which time it had completed a total of nineteen contractor demonstration flights and fifty-nine Air Force test flights.

On August 8,1949, Maj. Frank K. Everest, Jr., USAF, reached an altitude of 71,902 feet, the highest flight made by the little rocket airplane. It continued flight test operations until mid-1950, by which time it had completed a total of nineteen contractor demonstration flights and fifty-nine Air Force test flights. On August 26, 1950, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Hoyt Vandenberg presented the X-1 #1 to Alexander Wetmore, then Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. The X-1, General Vandenberg stated, "marked the end of the first great period of the air age, and the beginning of the second. In a few moments the subsonic period became history and the supersonic period was born."

On August 26, 1950, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Hoyt Vandenberg presented the X-1 #1 to Alexander Wetmore, then Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. The X-1, General Vandenberg stated, "marked the end of the first great period of the air age, and the beginning of the second. In a few moments the subsonic period became history and the supersonic period was born." The X-1 is powered by a Reaction Motors, Inc. Black Betsy four-chamber XLR-11 rocket engine producing a total of 6,000 lbs. thrust, The engine was not throttlable, but the four chambers could be fired individually to meter power in 1,500-lb. increments.

The X-1 is powered by a Reaction Motors, Inc. Black Betsy four-chamber XLR-11 rocket engine producing a total of 6,000 lbs. thrust, The engine was not throttlable, but the four chambers could be fired individually to meter power in 1,500-lb. increments. A significant innovation on the X-1 was its use of a "flying tail," or variable incidence tail plane in place of the usual elevators on the horizontal stabilizers to provide the necessary control authority during trans-sonic flight. In an interview with the PBS show NOVA, Yeager credited the incorporation of the flying tail into the F-86 Sabre jet for that plane's decisive advantage over the otherwise similar MiG-15 during combat in the Korean War.

A significant innovation on the X-1 was its use of a "flying tail," or variable incidence tail plane in place of the usual elevators on the horizontal stabilizers to provide the necessary control authority during trans-sonic flight. In an interview with the PBS show NOVA, Yeager credited the incorporation of the flying tail into the F-86 Sabre jet for that plane's decisive advantage over the otherwise similar MiG-15 during combat in the Korean War. "When we got the airplane up to oh, about 96 percent of the speed of sound indicated, that was almost Mach 1," Yeager said on NOVA. "And when we went a little faster, the Mach meter went off the scale. And ah, when it did all the buffeting smoothed out, because of the supersonic flow of the whole airplane. And even I knew we had gotten above the speed of sound. And I let it accelerate on out to about 1.06 or 1.07, seven percent above the speed of sound, and the airplane flew quite well. And I got some elevator effectiveness back, but not very much."

"When we got the airplane up to oh, about 96 percent of the speed of sound indicated, that was almost Mach 1," Yeager said on NOVA. "And when we went a little faster, the Mach meter went off the scale. And ah, when it did all the buffeting smoothed out, because of the supersonic flow of the whole airplane. And even I knew we had gotten above the speed of sound. And I let it accelerate on out to about 1.06 or 1.07, seven percent above the speed of sound, and the airplane flew quite well. And I got some elevator effectiveness back, but not very much." The X-1's radar beacon contributed to the telemetry from the plane sent to engineers on the ground. NACA engineer De Beeler reported tracking the X-1's data during Yeager's barrier-breaking flight and being surprised by the resulting sonic boom.

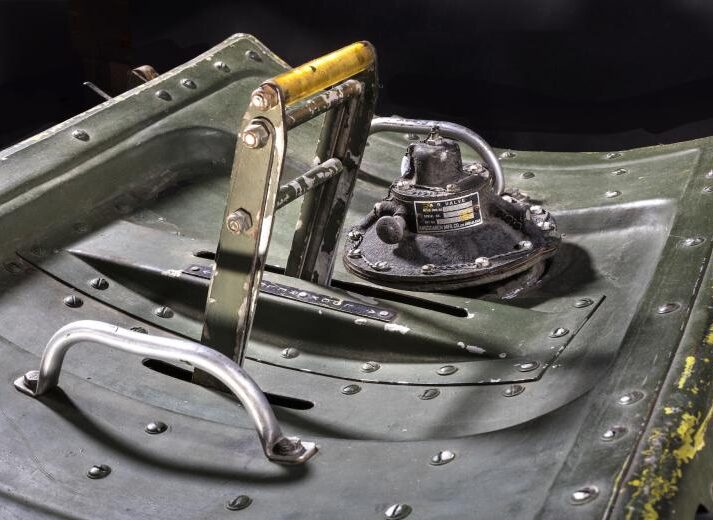

The X-1's radar beacon contributed to the telemetry from the plane sent to engineers on the ground. NACA engineer De Beeler reported tracking the X-1's data during Yeager's barrier-breaking flight and being surprised by the resulting sonic boom. As shown in the film, "The Right Stuff," Yeager broke ribs the night before the flight when his horse hit a fence. This left him unable to operate the lever latching the X-1's hatch with his right arm. He improvised, using a broom handle to operate it with his left hand instead.

As shown in the film, "The Right Stuff," Yeager broke ribs the night before the flight when his horse hit a fence. This left him unable to operate the lever latching the X-1's hatch with his right arm. He improvised, using a broom handle to operate it with his left hand instead. Bell test pilot Chalmers "Slick" Goodlin experienced a fire while flying the X-1 before Yeager's flight. "Shortly after I accelerated, the fire warning light came on," he said on NOVA. "And that caused the adrenaline to flow. And so I immediately shut off the rocket motor and called Dick Frost on the radio, who was flying the chase plane, and asked him if he could see any fire—that my fire warning light had come on. And of course, he was way behind me and said he couldn't see any evidence of fire. But after I had slowed down, why he could pull up behind me and he could still see no evidence of fire, but my fire warning light was still on. So I dumped the rest of the fuel and went back to the landing area and set the airplane down. And sure enough, we had sustained a rather serious fire in the engine compartment."

Bell test pilot Chalmers "Slick" Goodlin experienced a fire while flying the X-1 before Yeager's flight. "Shortly after I accelerated, the fire warning light came on," he said on NOVA. "And that caused the adrenaline to flow. And so I immediately shut off the rocket motor and called Dick Frost on the radio, who was flying the chase plane, and asked him if he could see any fire—that my fire warning light had come on. And of course, he was way behind me and said he couldn't see any evidence of fire. But after I had slowed down, why he could pull up behind me and he could still see no evidence of fire, but my fire warning light was still on. So I dumped the rest of the fuel and went back to the landing area and set the airplane down. And sure enough, we had sustained a rather serious fire in the engine compartment." "The X-1 was carried aloft in the bomb bay of a B-29," Goodlin recalled on NOVA. "And the procedure of going down the ladder and crawling into the X-1 at 8,000 feet and then sealing the door and being carried still higher to 28,000 feet, it was rather exciting, you know. I had no apprehension about it because we had no rocket fuel on board. And so when we got to altitude and went through the normal procedure of countdown and here I was in a very tiny cockpit and it was very dark, and all of a sudden when the X-1 was released from the B-29 I was in bright sunlight and I could hear nothing, it was so silent."

"The X-1 was carried aloft in the bomb bay of a B-29," Goodlin recalled on NOVA. "And the procedure of going down the ladder and crawling into the X-1 at 8,000 feet and then sealing the door and being carried still higher to 28,000 feet, it was rather exciting, you know. I had no apprehension about it because we had no rocket fuel on board. And so when we got to altitude and went through the normal procedure of countdown and here I was in a very tiny cockpit and it was very dark, and all of a sudden when the X-1 was released from the B-29 I was in bright sunlight and I could hear nothing, it was so silent." "Your emotions on something like that—you're too busy staying on top of the dome regulators and watching the chamber pressures and doing everything you're supposed to," Yeager recalled on NOVA. "And you might say I was a little bit disappointed it didn't blow up. That's about the only way to say—hell, it's a piece of cake."

"Your emotions on something like that—you're too busy staying on top of the dome regulators and watching the chamber pressures and doing everything you're supposed to," Yeager recalled on NOVA. "And you might say I was a little bit disappointed it didn't blow up. That's about the only way to say—hell, it's a piece of cake." "When I was assigned to the X-1 and, and was flying it I gave no thought to the outcome of whether the airplane would blow up or something would happen to me," Yeager stated. "It wasn't my job to think about that. It was my job to do the flying."

"When I was assigned to the X-1 and, and was flying it I gave no thought to the outcome of whether the airplane would blow up or something would happen to me," Yeager stated. "It wasn't my job to think about that. It was my job to do the flying." When things go wrong, the X-1's pilot needs to dump the plane's fuel before landing.

When things go wrong, the X-1's pilot needs to dump the plane's fuel before landing. "We had four positions on the rocket engine for each rocket chamber," explained Goodlin. "And to fire up one rocket. And of course, the first time I did it, it was like being hit in the back with a lead boot. And the aircraft accelerated very, very rapidly. And of course as one increased the thrust by adding more rocket positions—actuating more rocket positions—well, the aircraft could go very fast indeed, and quickly leave behind the B-29 and the chase plane."

"We had four positions on the rocket engine for each rocket chamber," explained Goodlin. "And to fire up one rocket. And of course, the first time I did it, it was like being hit in the back with a lead boot. And the aircraft accelerated very, very rapidly. And of course as one increased the thrust by adding more rocket positions—actuating more rocket positions—well, the aircraft could go very fast indeed, and quickly leave behind the B-29 and the chase plane." The X-1 provenance is displayed by its identification badges.

The X-1 provenance is displayed by its identification badges. Yeager was reunited with his old friend, along with the National Air & Space Museum staff, during a 2015 visit to the museum.

Yeager was reunited with his old friend, along with the National Air & Space Museum staff, during a 2015 visit to the museum. "It was a very delightful airplane to fly, as a matter of fact," Goodlin recalled. "It had the handling characteristics of a fighter plane. And it was very agile. I had no complaints about the flying qualities of the airplane at all."

"It was a very delightful airplane to fly, as a matter of fact," Goodlin recalled. "It had the handling characteristics of a fighter plane. And it was very agile. I had no complaints about the flying qualities of the airplane at all." The performance penalties and safety hazards associated with operating rocket-propelled aircraft from the ground caused mission planners to resort to air-launching instead. Nevertheless, on January 5,1949, the X-1 #1 Glamorous Glennis successfully completed a ground takeoff from Muroc Dry Lake, piloted by Chuck Yeager.

The performance penalties and safety hazards associated with operating rocket-propelled aircraft from the ground caused mission planners to resort to air-launching instead. Nevertheless, on January 5,1949, the X-1 #1 Glamorous Glennis successfully completed a ground takeoff from Muroc Dry Lake, piloted by Chuck Yeager.

Slide inside the cockpit with this gallery of the famous “Glamorous Glennis” Bell X-1 rocket plane that first broke the sound barrier.

Most of us are familiar with the bright orange, bullet-shaped Bell X-1 rocketship that legendary test pilot Chuck Yeager used to break the sound barrier for the first time on Oct. 14, 1947. Some of us may recall seeing the flight re-enacted in the fantastic film, “The Right Stuff,” which seems to be a mostly accurate portrayal of the event.

But the Bell X-1 that Yeager flew has hung from the rafters of the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum since it opened in 1976, so we couldn’t see many of the plane’s details up close.

Fortunately, Smithsonian has helped bring us closer to the famous plane by releasing photos for us to enjoy.

Source: https://www.designnews.com/industry/close-and-personal-supersonic-bell-x-1-rocket-plane

Related story would be of Brig Gen Frank Kendal Everest Jr. Who flew some of the Bell x series to just under mach 3. I was his administrative officer when as a My. Col. he was Commander of the 461st Fighter Squadron at Hahn AFB Germany in1957-58.