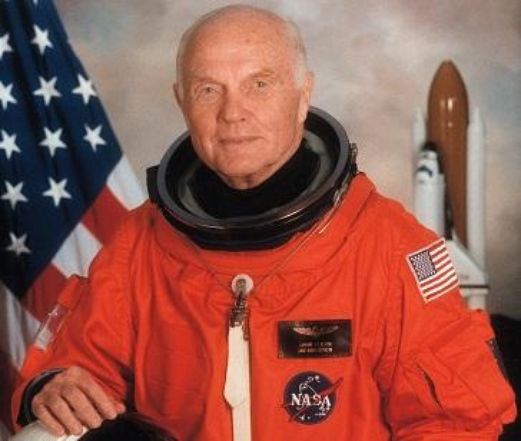

The first American to orbit the earth, and later a four-term U.S. senator from Ohio, died Thursday.

John Glenn died at the age of 95. One of the Mercury 7, he left the space race to pursue his political passions and became a U.S. senator. He finally returned to space in 1998 on a mission intended to study how space travel affects aging.

CINCINNATI — Over the long arc of John Glenn’s life, it proved impossible to ever ask him to do something for his country. No matter the mission, no matter the risk, he had already stepped forward, his hand raised, his jaw set, ready to go.

Glenn, the first American to orbit the earth, and later a four-term U.S. senator from Ohio, died Thursday at the Ohio State Cancer Center. He was 95.

Glenn became a hero in World War II and Korea, flying an astounding 149 combat missions in the two conflicts. He earned the Distinguished Flying Cross on six occasions and an Air Medal with 18 clusters. In Korea, he downed three Russian MIGs in air-to-air combat during the last nine days of that war. Ted Williams was sometimes his wing man.

He was, at that time, just another American who had served his country. But after the war, he heard about the space program, an outrageous idea of risk and service open to military test pilots. Of course, he was interested. After rigorous and competitive testing Glenn was chosen as one of the Mercury Seven, America’s first astronauts.

On April 8, 1959, Glenn was introduced at a press conference with Scott Carpenter, Walter M. Schirra, Jr., Alan B. Shepard, Jr., L. Gordon Cooper, Virgil “Gus” Grissom, and Donald “Deke” Slayton as the country’s Project Mercury astronauts. Glenn, who was the last surviving member of the group, a wore a bow tie.

To understand why John Glenn became so important in America, it is important to remember how badly the United States was losing the space race in the early 1960s. The Soviet Union had pulled ahead in this Cold War battle when it launched Sputnik, the first man-made object to be placed into orbit. It then made a mockery of the American program by sending the first human being, Yuri Gagarin, into orbit. Then the Soviets sent a second cosmonaut into orbit.

So all of America was watching at 9:47 in the morning on Feb. 20, 1962. Sitting in the cramped quarters of the Friendship 7 spacecraft, Glenn took off from Cape Canaveral. Scott Carpenter, the backup astronaut for the mission, famously said: “Godspeed, John Glenn.”

Astronaut Glenn climbed into space, circled the globe three times, and then dropped down into the Atlantic Ocean. The flight took all of 4 hours, 55 minutes and 23 seconds, but it changed the space race and restored American pride.

President John F. Kennedy watched the news from the Oval Office, and then came out and described Glenn as: “The type of American of whom we are most proud.”

Space travel then held far more unknowns that it does today. For example, “ophthalmologists were literally concerned at that time that your eyes might change shape and your vision might change enough you couldn’t even see the instrument panel enough to make an emergency re-entry if you had to,” Glenn said during the 2012 celebration of the 50th anniversary of his flight.

“They were enough concerned about it, we actually put a little, miniaturized eye chart at the top of the instrument panel,” Glenn said, according to an account of the celebration on Space.com. “And that’s still in Friendship 7, up in the Smithsonian (National Air and Space Museum).”

As Glenn prepared to re-enter the atmosphere, mission managers told him that Friendship 7’s protective heat shield might have come loose. And if the shield came off, the capsule would almost certainly burn up, killing Glenn.

Strapped to the outside of the spacecraft was a package of small retro-rockets, which were designed to help slow the capsule’s re-entry. Glenn was told not to jettison the rockets after firing them, in the hopes that the straps would help hold the heat shield on.

During re-entry, “there were flaming chunks of the retro-pack burning off and coming back by the window,” Glenn is quoted as telling Space.com. “I didn’t know for sure whether it was the retro-pack or the heat shield, but there wasn’t anything I could do about it either way, except just keep trying to work and keep the spacecraft on its actual best attitude coming back in.”

When Glenn returned, the nation and the free world celebrated on a historic scale. On Feb. 23, Vice President Lyndon Johnson escorted Glenn back to Patrick Air Force Base in Florida. Glenn, his family and Johnson then drove back to Cape Canaveral. The streets were lined with people the entire 18 miles. That afternoon, Glenn met with Kennedy who presented him with NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal.

On Feb. 26, John and Annie Glenn rode in an open car through the streets of Washington. At the Capital Building, Glenn gave a speech to a joint session of Congress.

Then Glenn and some of the other Mercury astronauts rode down Broadway in New York City. On a cold, miserable day, the sky was filled with ticker tape. Mayor Robert Wagner put the crowd at 4 million people, the largest in history at that time.

Glenn was 40 years old and soon became aware of the widely-held belief that the astronaut was too valuable as an icon to risk in space flight. But his career in public service was only at the halfway point.

In the months after his orbit, Glenn became close with President Kennedy and Robert Kennedy, who then was attorney general. They began to urge him to run for office. The Kennedys believed that being a popular astronaut was a great way to garner votes.

Two years after circling the globe, and six weeks after the assassination of President Kennedy, Glenn resigned from NASA. The next day, he announced that he was going home to Ohio to be a politician.

Returning made perfect sense. For a man who had circled the globe, nobody ever represented small-town Ohio more than John Glenn.

He was born in 1921 in Cambridge, Ohio, the son of John Sr. and Clara. Two years later, the family moved to New Concord where his father opened a plumbing business. Glenn would later say of his childhood: “A boy could not have had a more idyllic early childhood than I did.”

Glenn’s first flight was in Ohio when he was 8 years old. A barnstorming pilot in an open-cockpit plane took Glenn and his father up for a flight. The future spaceman was never the same.

Glenn went to the New Concord High School where he played varsity football, basketball, and tennis and was president of his junior class. He played in the town band, and had the lead role in the senior class play.

In 1939, Glenn graduated from New Concord High, which was later named John Glenn High School. It is one of a least five high schools in the country with that name.

Glenn then went to Muskingum College, just down the road from his home. In his sophomore year in college, Glenn had a chance to learn how to fly through the Civilian Pilot Training Program funded by the U.S. Department of Commerce. The program paid the cost of the flight instructions and gave college credits in physics. Glenn applied, was accepted, and earned his private pilot’s license on June 26, 1941.

But the most important thing to ever happen to Glenn in Ohio was meeting Anna Margaret Castor. She was always known as Annie, the daughter of town dentist. The Glenns and Castors were good friends. John and Annie were around each other often. They started dating in high school and were married on April 6, 1943. They had two children, John David Glenn and Carolyn Ann Glenn.

Despite his hometown appeal, his war record, and his status as an iconic astronaut, Glenn’s political career could not have had a worse beginning.

Glenn entered the Democratic primary in Ohio in 1964 for a seat in the U.S. Senateheld by Democratic incumbent Stephen M. Young.

First, Glenn was derided for not paying his dues. U.S. Rep. Charles Vanik, a fellow Democrat, said he had urged Glenn to start smaller in the political arena. “Instead, he has chosen to enter politics at the very top of a space platform built by the taxpayers of the United States,” Vanik said after Glenn’s announcement. Then Vanik continued. “The high office of the U.S. senator from the state of Ohio should not be made a hero’s pawn, no matter the breadth of our gratitude. This grave responsibility, so vital to the state and to the nation, should not be invested to the unprepared.”

Then it got worse. Less than a month into the race, a bathroom rug slipped under his feet, and Glenn hit his head against an unforgiving tub. This simple fall proved devastating and he could not campaign. It would take nearly a year to recover.

Glenn dropped out of the race, began to work as a consultant with NASA and as vice president of Royal Crown Cola. Two years later, he was named the president of the company.

In 1970, Glenn ran again, this time for the seat Young was stepping down from at the end of his term. Glenn ran in the primary against Cleveland real estate and parking magnate Howard Metzenbaum, who had the support of the state Democratic party and the unions.

Metzenbaum, who ran Young’s successful campaign in 1964 against Glenn, had more money and was better organized. He beat Glenn in a close primary, but then lost in the general election to Republican Robert Taft Jr.

In 1974, Glenn tried to get the Senate seat that opened after William Saxbe resigned his Senate seat after being named President Richard Nixon’s attorney general. But Gov. John Gilligan chose Metzenbaum instead.

Glenn went back to Royal Crown, but his dreams of the Senate survived. He got another shot at Metzenbaum. This time, Metzenbaum made a mistake. In a speech in Toledo, Metzenbaum said Glenn did not deserve Ohio’s vote because he “never worked for a living.”

It is unclear exactly what Metzenbaum meant when he made the statement. He was probably comparing his impressive work experience to Glenn’s, which was less impressive. But days later, during a debate, Glenn pounced and delivered what would be called his “Gold Star Mother’s” speech. The speech was clearly written, well practiced and completely devastating. It showed that Glenn, a man sometimes described as a Boy Scout, also had a sharp edge.

His speech that day became legend in Ohio political circles, Glenn said.

“I served 23 years in the U.S. Marine Corps. I served through two wars. I flew 149 missions. My plane was hit by antiaircraft fire on 12 different occasions. I was in the space program. It wasn’t my checkbook; it was my life on the line. It was not a nine to five job where I took time off to take the daily cash receipts to the bank.

“I ask you to go with me. … as I went the other day to a Veterans hospital and look at those men with their mangled bodies in the eye and tell them they didn’t hold a job. You go with me to the space program and go as I have gone to the widows and orphans of Ed White, Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee and you look those kids in the eye and tell them that their dad didn’t hold a job.

“You go with me on Memorial Day, coming up, and you stand in Arlington National Cemetery, where I have more friends than I’d like to remember and you watch those waving flags. You stand there, and you think about this nation, and you tell me that those people didn’t have a job, I’ll tell you, Howard Metzenbaum, you should be on your knees every day of your life thanking God that there were some men – some men – who held a job. And they required a dedication to purpose, a love of country and a dedication to duty that was more important than life itself. And their self-sacrifice is what made this country possible. I have held a job, Howard. What about you?”

Glenn won the primary and the general election and would represent Ohio for 24 years. During his time in the Senate, he was chief author of the 1978 Nonproliferation Act, served as chairman of the Committee on Governmental Affairs from 1987 until 1995, sat on the Foreign Relations and Armed Services committees and the Special Committee on Aging.

In 1984, Glenn ran for president; Metzenbaum, who won election to the Senate in 1976, endorsed him. But he dropped out when his campaign never gained much traction. Walter Mondale would win the Democratic nomination but lost in a landslide lost to Ronald Reagan in the general election.

After the presidential bid, Glenn earned some rare bad headlines, for being part of the so-called Keating Five group of senators. The collapse of a large savings and loan in California led by former Cincinnatian Charles H. Keating Jr. cost the FDIC roughly $3 billion in what at the time was the single biggest bank failure in American history.

In 1989, federal regulators seized control of the S&L and Keating’s other holdings, accusing him of looting Lincoln Savings at taxpayer expense, sinking money into risky ventures and cheating the company’s investors.

The regulators filed a $1.1 billion civil racketeering and fraud lawsuit against Keating, accusing him of siphoning Lincoln’s deposits to his family and into political campaigns (including a total of $1.4 million to Glenn and the four other senators). Keating also was convicted of criminal wire and bankruptcy fraud charges.

The senators were accused of improperly intervening with federal regulators on Keating’s behalf. A two-year investigation resulted in all of the senators emerging legally unscathed. Reporters asked Keating, who served four years in prison for his crimes, if his contributions had paid off and he replied, “I want to say in the most forceful way I can: I certainly hope so.”

However, Glenn would have one more high-profile act of service to his country. This time, he wanted to help and inspire older people.

On Oct. 29, 1998, just months from the end of his time in the Senate, Glenn became the oldest person ever to go into space. He was 77 years old when he finally got his second mission, this time aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery.

Glenn underwent a series of medical tests before, during, and after the flight. NASA scientists tested Glenn’s balance and perception, his protein metabolism, and his heart and blood flow. Glenn also wore a harness during many of his nights in space to monitor sleep disorders, another common problem in space travel.

This flight involved 134 orbits of the earth, instead of three trips around he took back in 1962. But he said the same thing to his wife he used to tell her every time he would embark on a dangerous mission in war or in space. “I’m just going down to the corner store to get a pack of gum,” Glenn would say. And she responded: “Don’t be long.” (Before he took his flight on the space shuttle, Glenn actually gave his wife a pack of gum to keep while he was away.)

In 1998, Glenn began working in earnest for Ohio State University, with the creation of the John Glenn Institute for Public Service and Public Policy. In 2006, the University founded the John Glenn School of Public Affairs.

The founding principals for the school may have been determined in 1997 when Glenn donated his personal and Senate papers to Ohio State. That day, Glenn said: “If there is one thing I’ve learned in my years on this planet, it’s that the happiest and most fulfilled people I’ve known are those who devoted themselves to something bigger and more profound than merely their own self-interest.”